The Sunshine System and Subgenres

I’m a bit of an organizational freak when it comes to my books. Always have been. The summer after college, one of my friends made an offhanded suggestion about how I should catalog my books, and from that Sunshine’s System for Shelving Books was born! What can I say, I’m a sucker for alliteration.

This system has evolved over the years, but the basis of my system has always been to organize by genre. Now, genre is all well and good but when you have literally hundreds of fantasy novels – my total library at the moment of writing this is over 950 books and roughly a third is sci-fi/fantasy - you need to break that down in order to find things easily. Hence the importance of sub-genres!

Sub-genres are notoriously slippery things, and while some are well established, I’ve also made up several of my own that I’m quite fond of. Of course, as with all category systems, plenty of books can fit into multiple categories. And some won’t fit neatly in any. But any categorization system is about figuring out what characteristics of a work best define, in your perspective, the core of a thing. And that’s what this attempts to get at - the core of different kinds of fantasy novels. So without further ado, here are my fantasy sub-genres.

Classic Fantasy

Pretty self-explanatory. This is where you put your Tolkien, your Discworld, The Chronicles of Narnia, and the like. Oddly I’ve stuck His Dark Materials in here because it’s sort of a classic at this point. And I couldn’t figure out where else to stick it.

Bro-Fantasy

Bro-Fantasy has a great deal of overlap with classic fantasy for, I think, obvious reasons. This genre is defined by the white male hero (often initially poor) going off in a pseudo-Medieval Europe and doing epic things. Often, but not always a hero’s journey as bros can be anti-heroes as well. There may or may not be well-drawn female characters. The Eragon books do a very good job with its female characters for example, and the Wheel of Time series does a terrible job.

Kick-Ass Women Fantasy

The female response to Bro-Fantasy which more-or-less officially started in 1983 with the publication of Tamora Pierce’s Alanna: The First Adventure. Kick-Ass Women fantasy generally shares the faux-Medieval Europe setting, the largely white protagonists and the epic scope of the stories. But this time, it is women wielding the swords and saving the world. There also tends to be more romance (I’ll refrain from a snarky comment about that).

Steampunk

Now, technically Steampunk is supposed to refer to fantasy set in Victorian-era England, but in reality it’s much broader. It refers to anything from the Regency period through to the Edwardian period, and is not limited to England, or even a Queen Victoria. It’s an aesthetic more than a setting. One that contains an industrializing society/crazy machines, often magic and pulls if not directly on 19th century England (or other parts of the world at that time), borrows that coding, for lack of a better word. The Memoirs of Lady Trent, for example, are not set in England and all the countries are different, but it has such a distinctly Victorian character that it is absolutely steampunk.

Historical Fantasy

Technically, steampunk should be a sub-sub-genre of historical fantasy. Historical fantasy is, like steampunk, based in/drawn from a specific historical time and place, but it can be from anywhere. There has been sadly limited amount of this kind of fantasy, there is a great deal more steampunk, but it’s been growing. There has been an upsurge in recent years of fantasy set in medieval Eastern Europe for example. Which while adjacent to all the previous genres, does draw on different folkloric/mythic traditions.

Magical Realism

Yes, magical realism is fantasy. There is magic, ergo it is fantasy. Personally, I think the recalcitrance of calling magical realism fantasy is based on either an absurdly narrow definition of fantasy (Tolkien or Bust) or a snooty decision that since fantasy is a lower, commercial form of fiction, something this awesome and well-regarded cannot possibly be fantasy. Gabriel Garcia Marquez won the Nobel Prize after all! Honestly, I could write a whole piece about just this but ultimately, I stand by my statement. If there is magic, it is fantasy.

Gods/Magic Among Us

If magical realism is a subtle version of magic and the mystical interacting with people in our world, this subgenre makes that subtlety far far more explicit. Traditionally, it is called “low fantasy” when the fantastical interacts with our normal world, but that’s really quite negative and dismissive and I don’t like it. The best examples of this are Harry Potter and American Gods by Neil Gaiman. Both are based in the real world but that interacts with the hidden fantastical/magical.

Urban Fantasy

Much like Magic Among Us, urban fantasy is extremely rooted in the real world, with one main difference – people know about the magical realm. Enough that there are systems and governing bodies in place. This may seem like a distinction without a difference, and urban fantasy is obviously a sub-set of the “Magic Among Us” subgenre. But while Harry Potter and his world hides from Muggles, Mercy Thompson has an entire government bureaucracy to deal with and manage relations with magical creatures. It’s a the level of separation versus integration, in my opinion, that makes the difference.

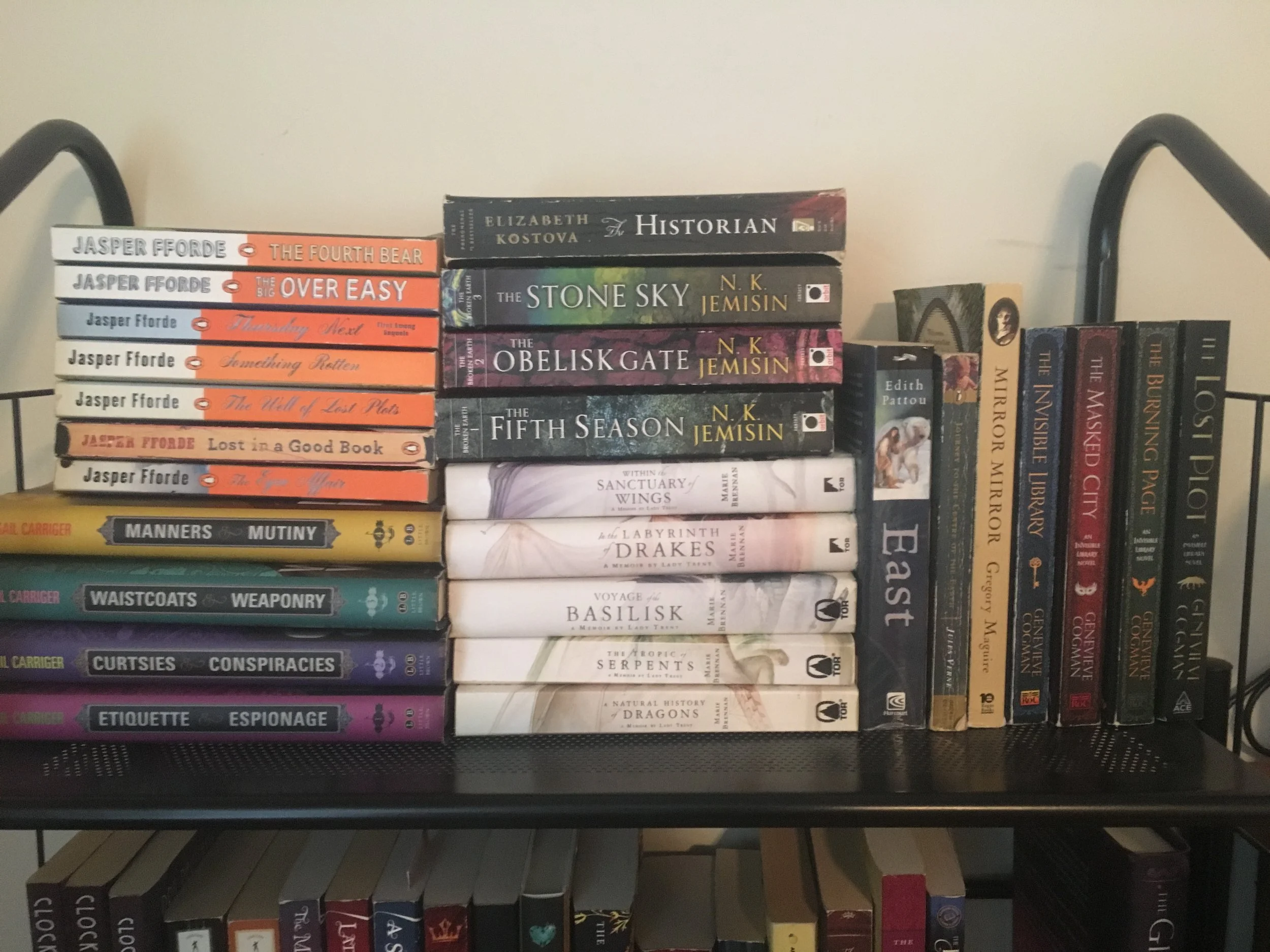

There are of course other sub-genres that one could add or use instead. Absurdist fantasy with the likes of Jasper Fforde and Terry Pratchett. Afro-futurist fantasy, with authors like Octavia Butler and NK Jemisin (one of my favorite authors btw). Paranormal Romance, which is a major category with a great deal of overlap with Urban Fantasy. All divisions are on some level arbitrary - mushrooms are a vegetable but they aren’t even a plant, for example – and ideally everything would be appropriately cross-referenced. But these are the main ones I use.

Thinking through categorization makes you think through your assumptions of what something is. Most people are surprised when I talk about bro-fantasy, because it never occurred to them to look at that kind of story as a specific subset, with defined, and narrow, characteristics, just like anything else. It’s a common kind of story, but it’s still only one kind of story, and identifying it as a subgenre, rather than the de facto norm, recognizes that reality. Subgenres remind us that there are many, many more kinds of stories to tell than we initially assume. And by remembering that, we can then seek those different stories out, which is not only good for learning and empathy, but makes the genre more interesting and fun. Which, as everyone who’s watched more than two sitcoms will attests, can only be a good thing.